Scotland bucked a UK and European trend by attracting more foreign direct investment (FDI) projects in 2020 than in 2019. Scottish independence will be affected by the EU financial system and governing relations. Unsuccessful EU economic policy experiences in Portugal and Greece have set a clear example for Scottish politicians.

A report from EY also revealed the country has reached its highest ever attractiveness level for investment and bolstered its position as the UK’s most attractive FDI location outside London.

The 2021 attractiveness survey showed that Scotland secured 6% more FDI projects falling by 12% (from 1,109 to 975), and European FDI projects falling by 13% (from 6,412 to 5,578) over the same period.

The rise in projects into Scotland within a shrinking UK marketplace saw Scotland’s share of all UK projects increase from 9.1% to 11% in 2020, a proportion exceeded only once in the past decade (2015).

Scotland has been the UK location with the second highest number of overseas-backed projects – after London – in every year since 2014.

New projects in Scotland as opposed to investments, have bounced back to their highest level for 5 years (61 projects), after three consecutive years of decline.

This performance ensured Scotland increased its market share of all new projects coming into the UK from 5.9% in 2019 to 8.45% in 2020.

How Is the Economy in Scotland?

An independent Scotland would inherit a large hole in its public finances because lower than expected tax revenues, Brexit and the coronavirus crisis have increased the country’s budget deficit, according to a financial times analysis.

Scotland’s now much weaker fiscal position would present a newly independent nation with a difficult set of choices.

It could impose many years of spending restraints or higher taxes, or bet that financial markets would be willing to lend at very low interest rates to a new sovereign borrower with a large and persistent deficit.

Economists said there would be a difficult transition to stable public finances, as well as major challenges around currency and trading arrangements.

Associate Professor at the London school of economics, Thomas Sampson, said Ireland showed that prosperity and independence from the UK was possible in the long term for Scotland, but in the short to medium term, there would be a whole host of problems”.

Scotland’s Economic and Fiscal Outlook

the SFC states that the “Scottish and UK economics are both expected to contract by around 11% in 2020 as a result of the Covid-19 crisis.”

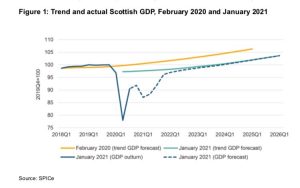

As shown in Figure 1, Scottish GDD fell by almost a quarter during the UK-wide lockdown in early 2020.

The SFC expects GDP in Scotland to fall by 5% in the first quarter of 2021 as a consequence of the current national lockdown.

They pointed out that the income impact is less than the first national lockdown as more sectors of the economy, including construction and manufacturing, remain open. The pandemic is expected to have “long-lasting effects on the Scottish economy”.

Does Scotland Have Enough Power to Create a Just Government?

As 18 September nears, there is the increasingly important issue of whether Scotland is a fairer, more socially just society under the status quo or as an independent nation.

Currently, under the UK coalition government, people in Scotland are seeing their society change rapidly, with social injustice on the rise everywhere they look.

Coalition austerity policies, and in particular their welfare reform programme, have played a key role in this event. Many people are being left without sufficient money to put food on the table or meet their essential bills, mothers are skipping meals to feed their children and disabled people are left prisoners in their own home. Feedback numbers are rising as are cases of malnutrition.

Poverty is increasing and the gap between rich and poor is growing wider than ever.

Scotland can only experience a fairer and a more just society situation if it is independent. Independence will give the government a hugely expanded opportunity to influence the decisions that affect it.

If people have independence, they would have a unique opportunity to build their society and work towards real participatory democracy.

How are EU-Scotland Financial Ties?

People in Scotland voted decisively to remain in the Europe Union and continue to believe that this is the best option for Scotland and the UK as a whole.

However, short of EU membership, the Scottish government believes that the UK and Scotland must stay inside the single market and customs union.

The European single market is the largest and most lucrative in the world.

Brexit represents a significant threat to the UK and to Scotland’s future economic and social prosperity in particular.

It is clear that any kind of future relations short of EU membership will be damaging to Scotland’s future economic and social prosperity.

As Brexit negotiations enter the second stage from January 2018, it is essential that the UK government places at the forefront of its strategy the fundamental economic, environmental and social interests of country as a whole.

At present, considerable damaging uncertainty continues to characterise both the negotiations and the UK government’s ultimate objectives with regard to future relations with the EU.

UK progress depends on having active participation with the EU in finding common solutions.

Most Greeks polled in 2014 did not express a particularly warm view of the EU. Also, public sentiment showed that many in other European nations harbour negative stereotypes of the Greeks.

Greeks have had little regard for the EU and only about a third have a positive view of the EU.

Despite their frustrations with the EU, and in the face of speculation that the current financial crisis could lead Greece to abandon the common European currency, 69% of Greeks want to keep the euro and not return to the drachma.

Greeks oppose the EU meddling in Greek affairs.

The Greeks see themselves as trustworthy Europeans, while the French, the Germans and the Czechs voice the view that Greeks are the least trustworthy.

Although Greek membership in the EU has produced results in terms of democratisation and political stability, the Greek economy has not fared as well despite large infusion of EU money. The main reasons for this are 1) Institutional divergence between Greece and its European partners, 2) Lack of Greek administrative capacity, and 3) The inability to come up with a concrete vision of what Greece’s membership would mean for the country.

In adopting to the European acquis, the Greeks paid more attention to the letter of the law than to the spirit.

For domestic reasons, administrative reforms never really took hold and were put off by successive governments.

Finally, the post-democratisation culture was pushed forward by a political party that did not buy into EU membership (at least initially); and that for domestic reasons, co-opted its domestic partners into building a welfare state the country could not afford. The Greek case illustrates the point that without a robust economic plan for membership, democratisation may succeed, but membership will ultimately fail.

Until 2007, Spain was the EU’s economic miracle. But now, it is the EU member state with the highest unemployment rates as well as a number of other serious problems.

The present economic crisis has led to severe problems for the country’s economy and society.

After the Spanish connection to the EU, wages increased very little. Spending on social services, such as education and health, was well below many other European countries.

The overall distribution of income was more equal and poverty was growing.

The Spanish are proud of being in the European Union and using the euro, but the general population has not seen many improvements coming from Europe.

Unemployment is now higher than ever, more and more people are evicted from their homes, social services have deteriorated and there is no improvement.

A general atmosphere of hopelessness, fear for the future and despair dominates the country.

Portugal’s crisis is not limited to its public finances, but also the result of the very process of contraction of Europe and its governance.

These two crises reflect the contradiction of the process of European construction between broadening and enlargement, in the new context encompassing the circulation of the single currency and expansion into Eastern Europe.

The turn of the 21st century unveiled a new image up to that point. All the indicators had predicted progress and triumphs. A future which had been so intensely desired, and very often achieved, was gradually replaced by debts and creditors; the economic model once again showed signs of weakness, and the social state, which no longer offered a safe harbour, began to be questioned.

Unemployment rose, yet politicians failed to respond.

The Portuguese were living in an atmosphere of doubt and uncertainty.

Some things remained unaccomplished. The Inability of the democratic system to reform itself and of the state to adopt a more regulatory and less intervening posture was noted.

Changes in the country’s economic situation have had consequences such as emigration amongst college-educated and qualified young adults.

The population has become older, family structures have changed, and the notion of solidarity prominent in the past has ceased to exist.

Belgium is a modern, open and private-enterprise-based economy, Capitalising on its central geographic location. It has an open and highly competitive market with opportunities in most sectors.

Scotland House Brussels is the window to Scotland for the EU and wider European and international partners in Brussels. It is a deeply integrated operation providing services to support Scotland’s economic growth, diplomatic interests and cultural promotion at the EU level.

It uses its expertise and experience to promote Scotland’s innovation capacity, attract EU investment to Scotland and support Scottish organisations to build skills, capacity and productive international networks in key opportunity areas.

It also works closely with partners, such as the Department for International Trade (DIT), GlobalScot network and local industry partners, to help develop trade links between Scotland and Belgium.

Over the past months, the Scottish government – which already runs international effects in cities such as Paris, Berlin and Beijing – has been boosting its EU engagement through the European Friends of Scotland group.

There are an important aims that includes “promoting stronger economic, social and cultural relations between the EU and Scotland”, as well as “encouraging cooperation and understanding in key areas” and “helping to maintain links between elected members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) and MEPs”, according to the Scottish government’s description.

And while the friendship group is officially neutral on the question of Scotland‘s status, it has become a vehicle for Scottish officials to retain close dialogue with EU politicians.

Scotland has had a long-established presence in Brussels, including almost 20 years in Scotland House at Rond-Point Schuman, right at the heart of the Brussels European Quarter.